At 7:42 a.m. in eastern Shanghai, the city hums the way great cities do — trucks growl past, buses hiss, office workers hurry toward subway entrances. A survey engineer named Li adjusts a laser level on Yan’an Road, its green line flickering across the morning air. Two decades ago, this patch of concrete was quietly sinking. Not collapsing — just settling, millimeter by millimeter, year after year.

Today, the numbers on Li’s monitor barely move.

No sirens announced the change. No headlines broke the story. But far below, nearly a kilometer underground, Shanghai engineers have been doing something almost paradoxical: pumping water back into the earth.

The result? Skyscrapers stay upright. Flood defenses hold their line. And one of the world’s most densely built cities has — quite literally — stopped sinking.

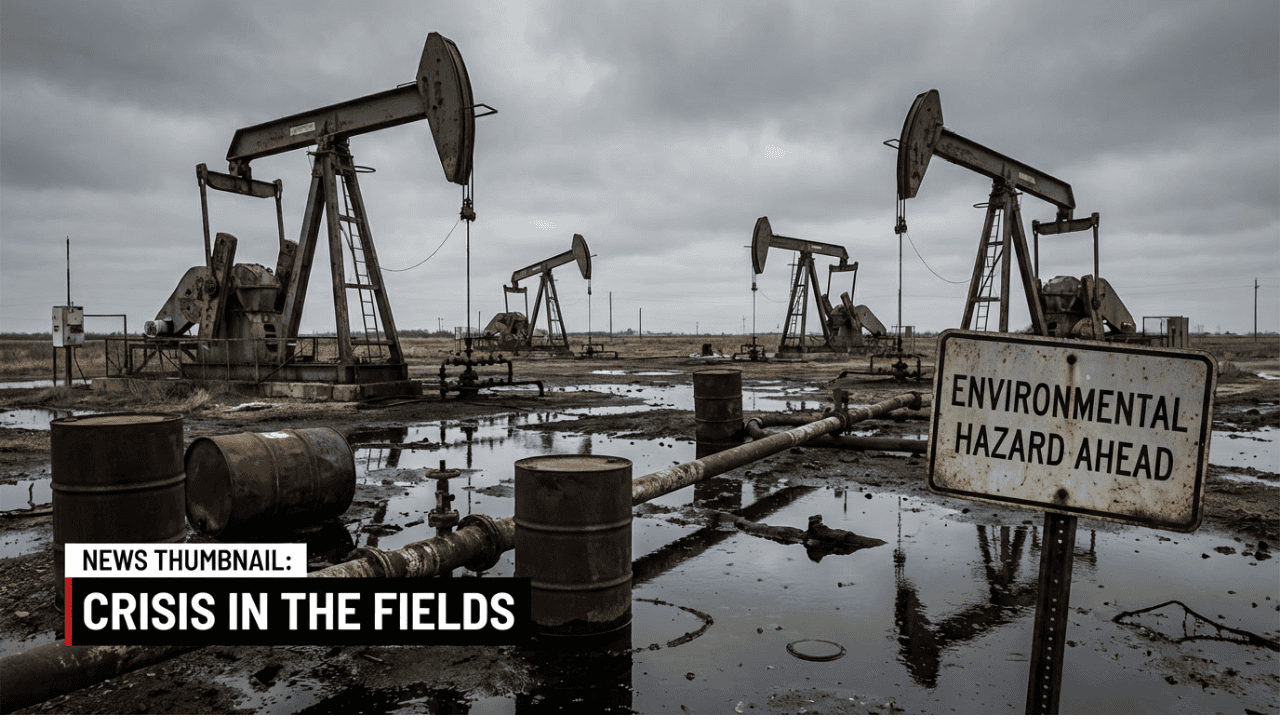

The Hidden Crisis Beneath Cities

Land subsidence is one of those threats that never make breaking news. It doesn’t strike like an earthquake or roar like a storm. It creeps.

Doors start sticking. Drains tilt in odd directions. Floodwaters reach a little higher than they used to.

The cause is deceptively simple physics: when fluids are removed from the ground faster than they’re replaced, the soil compacts.

In aquifers and oil-bearing layers, water and gas act like internal scaffolding. Take them out, and the scaffolding weakens. The ground begins to settle under the city’s own weight.

It’s a slow-motion disaster that has reshaped some of the world’s great capitals.

| City | Peak Subsidence Rate | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Mexico City | Up to 40 cm/year | Groundwater extraction |

| Jakarta | 20–25 cm/year | Groundwater extraction, building load |

| Shanghai (20th century) | >2 m total | Groundwater and oil withdrawal |

| Tokyo (mid-1900s) | ~20 cm/year | Groundwater extraction |

In places like Mexico City, whole neighborhoods have sunk more than 10 meters since the early 1900s. Jakarta, built on swampy deltas, is now descending faster than global sea levels are rising — a key reason Indonesia is relocating its capital.

The Counterintuitive Fix

The idea that solved much of Shanghai’s problem sounds backward: stop taking fluids out, and start putting them back in.

Beginning in the late 1980s, the city’s engineers drilled a network of injection wells into depleted oil and gas reservoirs. Instead of pulling hydrocarbons, they pumped treated water underground — not to produce energy, but to restore balance.

Originally, petroleum engineers used this technique, known as water flooding, to force remaining oil toward production wells. But in Shanghai, scientists realized that refilling these geological layers under controlled pressure could do something else: hold up the city above.

By restoring pore pressure in rock and clay layers, water injection reduces the effective stress that causes compression. The land doesn’t “bounce back” — but the sinking slows dramatically.

Think of it as installing invisible hydraulic supports beneath the entire metropolis.

How It Works

At depth, the ground behaves like a stiff sponge. The grains of sediment bear part of the load, while water in the pores carries the rest.

When you pump that water out, more weight shifts to the grain skeleton, squeezing it tighter — the surface above settles. By pumping water back in, engineers raise pore pressure again, transferring some of the load back to the fluid.

It’s a delicate balance:

- Too little pressure, and subsidence continues.

- Too much, and you risk fracturing rock layers or triggering small tremors.

Modern injection programs use real-time monitoring — satellite radar, GPS sensors, and downhole gauges — to adjust injection rates daily.

Shanghai’s Slow Rescue

By the 1980s, some districts of Shanghai were sinking by 3–4 centimeters a year. Buildings tilted, pipelines cracked, and flood barriers had to be raised repeatedly.

Authorities first restricted groundwater extraction. Then, in the 1990s, they began recharging aquifers and depleted oil fields.

The results came quietly but decisively.

| Period | Average Subsidence Rate | Key Measure |

|---|---|---|

| 1950s–1980s | 20–30 mm/year | Extensive groundwater use |

| 1990s | <10 mm/year | Injection wells introduced |

| 2000s–Today | ~2–3 mm/year | Continuous monitoring and rebalancing |

By the 2010s, parts of the city had reached near-stability, sinking less than 2 millimeters per year — slower than the thickness of a coin.

It wasn’t a miracle cure. But it was enough to buy time: time to strengthen levees, rebuild drainage, and adapt construction codes to climate realities.

Not a Solution — a Delay

Even Shanghai’s engineers admit that water injection isn’t permanent salvation. Deep clay layers still compress slowly. Sea levels continue to climb. And the city’s vertical weight keeps increasing.

What the injections buy is time — the most precious commodity in climate adaptation.

As one hydrologist at a Jakarta planning workshop put it:

“What we sell cities isn’t a solution. It’s time — time for their children to still live here.”

Global Lessons

Other cities are taking notes.

- Tokyo stabilized much of its ground by recharging aquifers after banning deep groundwater extraction in the 1970s.

- Tianjin and Taipei are experimenting with similar controlled re-injection systems.

- In California’s San Joaquin Valley, pilot projects are using treated surface water to refill aquifers after decades of agricultural drawdown.

The science is universal: pressure lost must somehow be restored.

How Cities Manage It Safely

According to guidelines from the China Geological Survey and international geotechnical associations, effective water-injection programs follow key rules:

- Continuous monitoring via satellite interferometry and in-situ sensors.

- Conservative pressure limits to prevent fracturing.

- High-quality injected water, treated to avoid clogging pores or contaminating aquifers.

- Transparent data sharing among city planners, hydrologists, and utilities.

Failures, experts say, rarely come from the idea itself — but from impatience or poor oversight.

Cities on Borrowed Elevation

Walking through modern Shanghai — the marble lobbies, glass towers, and polished subway platforms — it’s easy to forget that the entire city sits on borrowed elevation. The ground beneath holds not just history, but hydraulic memory.

Water injection turns old oil fields into silent guardians. But their vigilance lasts only as long as humans maintain it.

Cities, after all, are bets on the future. And the earth beneath them remembers every drop we take — and every one we return.

FAQs

Does water injection completely stop land subsidence?

Not entirely. It usually slows subsidence from centimeters to millimeters per year, giving cities crucial time to adapt infrastructure and flood defenses.

Is water injection safe?

Yes, when carefully managed. Risks like fractures or minor seismicity arise only when pressures exceed conservative limits or monitoring fails.

Which cities have used this method successfully?

Shanghai and Tokyo are leading examples, with additional programs in Mexico City, Tianjin, and parts of California’s Central Valley.

How deep are these injection wells?

Typically several hundred meters to a kilometer deep, targeting depleted oil, gas, or confined aquifer layers.

Is this a long-term climate adaptation tool?

It’s a bridge strategy — not permanent, but effective at buying decades of safety while long-term flood and drainage systems catch up.