Water has always been a precious resource in the western United States—but now, it’s under serious threat. Climate change is reshaping how, when, and where water is available. From shrinking snowpacks to prolonged droughts, the West is facing a water crisis that’s becoming harder to ignore.

In this article, we’ll look into how climate change is affecting water resources in the western U.S., what that means for communities and ecosystems, and what can be done about it.

Overview

The western U.S. depends heavily on a delicate water cycle—snow falls in the mountains during winter, melts in the spring, and flows into rivers, reservoirs, and aquifers. But climate change is throwing that cycle off balance.

Warmer temperatures are melting snow earlier, reducing runoff in the summer when water is needed most. Droughts are lasting longer, rain is more unpredictable, and heatwaves are drying up rivers and lakes faster than ever.

This isn’t just about inconvenience. It’s about survival—for people, farms, cities, and ecosystems alike.

Snowpack

In the West, snowpack is everything. It acts like a natural reservoir, storing water in the winter and releasing it gradually through spring and summer.

But here’s the problem: rising temperatures are turning snow into rain. Less snow means less runoff, and what does fall is melting weeks earlier than it used to.

According to NOAA, snowpack levels in places like California’s Sierra Nevada have dropped by 20% or more over the last few decades. That’s a huge loss, especially when 60–80% of the region’s water supply comes from snowmelt.

Drought

If you’ve lived in the West lately, you’ve probably heard the word “megadrought.” It’s not just a media term—scientists use it to describe the severe, multi-decade drought gripping the region.

The current megadrought (which began around 2000) is considered the worst in over 1,200 years. Hotter temperatures from climate change have intensified this natural dry period, making it more extreme and harder to recover from.

The result? Dry reservoirs, stressed agriculture, water restrictions, and growing tensions between states over who gets how much.

Groundwater

When surface water runs dry, people turn to groundwater. But that’s not a long-term solution either.

In states like Arizona and California, groundwater pumping has increased dramatically in recent years. Aquifers are being depleted faster than they can recharge, causing wells to run dry and land to sink—a process known as subsidence.

Once these underground water sources are gone, they’re gone for good—or at least for thousands of years.

Agriculture

The western U.S. grows much of the nation’s food. But climate stress is making that harder by the year.

Less water means smaller harvests, fallowed fields, and financial losses for farmers. Crops like almonds, lettuce, and grapes need steady irrigation—but with shrinking supplies, growers are being forced to scale back or find new water sources.

Some farms are switching to less thirsty crops. Others are leaving agriculture altogether.

Ecosystems

It’s not just people who suffer. Fish, birds, and entire ecosystems are also feeling the pressure.

Low river flows and warmer water temperatures threaten species like salmon, which rely on cold streams to spawn. Drought and heatwaves have dried out wetlands that migrating birds depend on.

And forest fires—worsened by dry conditions—are damaging watersheds and increasing runoff pollution.

Cities

Urban areas are adapting, but not without challenges. Cities like Las Vegas, Phoenix, and Los Angeles have made major investments in water recycling, conservation, and efficiency.

But population growth is outpacing supply. With the Colorado River in crisis and reservoirs like Lake Mead hitting record lows, cities are being forced to rethink how they use every drop.

Some are turning to desalination and wastewater reuse. Others are tightening water restrictions for homes and businesses.

Colorado River

The Colorado River is the lifeblood of the West. It supplies water to over 40 million people and irrigates 5 million acres of farmland.

But it’s drying up—fast. Climate change has reduced the river’s flow by nearly 20% over the last century, and it’s expected to shrink even more.

Reservoirs like Lake Powell and Lake Mead, which store Colorado River water, are at historic lows. If levels drop too far, hydroelectric power and water supply systems could be disrupted.

Here’s a quick snapshot:

| Reservoir | Capacity % (2023) | Historical Avg |

|---|---|---|

| Lake Mead | ~30% | ~65% |

| Lake Powell | ~25% | ~60% |

Solutions

So what can be done? While the problem is massive, solutions do exist:

- Water conservation: Reduce waste in homes, industries, and agriculture

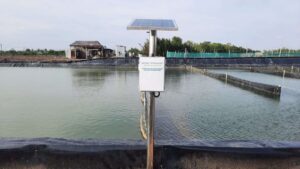

- Smart irrigation: Use drip systems and soil sensors on farms

- Recycling water: Treat and reuse wastewater for landscaping or industrial use

- Desalination: Turn seawater into drinking water (though expensive)

- Policy reform: Update water rights and interstate agreements to reflect today’s reality

- Climate action: Reduce greenhouse gas emissions to slow warming and drought intensity

Change won’t happen overnight. But with innovation, cooperation, and smart planning, the western U.S. can adapt—and thrive.

Water is no longer something we can take for granted in the West. Climate change is making it scarcer, more unpredictable, and harder to manage.

But it’s also pushing cities, farmers, and policymakers to innovate and adapt. The stakes are high—but so is the potential to build a more sustainable, water-smart future.

FAQs

How does climate change affect snowpack?

Warmer winters reduce snow and cause earlier melt.

What is a megadrought?

A long, severe drought lasting decades, worsened by climate change.

Why is groundwater use risky?

Overpumping depletes aquifers and causes land to sink.

How is agriculture impacted?

Less water means reduced crop yields and financial strain.

What are solutions to water shortages?

Conservation, recycling, policy reform, and climate action.